Casa Maravilla Lot 51, New Design

Degenkolb Dispatches Two Earthquake Reconnaissance Teams to Turkey

Degenkolb Engineers assembled two reconnaissance teams to survey the damage of the recent Turkey-Syria earthquake and its subsequent seismic events. On February 6, 2023, a 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck southern and central Turkey and the northern and western parts of Syria. The surrounding region sustained widespread damage and significant loss of life. Our engineers embarked on these trips to search for clues around why certain structures succumbed to ground motion versus others and to help advance the field’s knowledge of structural performance.

David Sommer—an Associate Principal in Seattle—led Team 1 who landed in Turkey on February 27th. Other team members included Jose Flores Ruiz (Associate Principal, Mexico), Jerry Luong (Design Engineer, Orange County), Kim Bocanegra (Designer, Sacramento), and Rafael Alaluf—Founder of EQRM International and former Degenkolb engineer based in Turkey.

Jen Gross—an Associate Principal in Oakland— led Team 2 who arrived in Turkey a week later on March 6th. Other members included Adam Hugo-Holman (Principal, San Francisco), Justin Tan (Project Engineer, Los Angeles), Anthony Ambrosio-Meir (Project Engineer, San Francisco), Rafael Alaluf from Team 1, and Baris Lostuvali—a Project Executive with The Boldt Company and Turkish national. Team 2 convened with Team 1 upon arrival.

During the trip, the teams were in close communication with the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and shared data via EERI Clearinghouse. Additionally, each team collaborated with non-profit organization, Build Change, to assess ways to support the local disaster relief and recovery efforts.

Both teams’ findings will be published throughout this week at https://degenkolb.com/ideas/

We are happy to share our findings with you. If you’re interested in having our engineers give a presentation about their conclusions, please contact Laurie Lumish at llumish@degenkolb.com.

Degenkolb Mexico Brings Seismic Expertise to Baja Peninsula

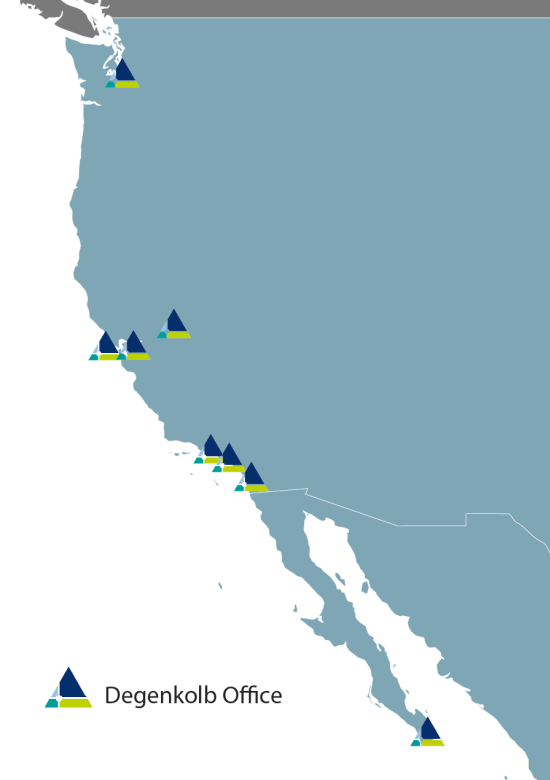

Degenkolb’s newest office is now open. Degenkolb Mexico (registered as DGKB ENGINEERS MEX) is the firm’s first office expansion internationally. Based in San José del Cabo in the state of Baja California Sur, the group’s onsite day to day operations will be led by Jose Antonio Flores Ruiz as Degenkolb Mexico’s Associate Principal and Engineering Manager. Daniel Zepeda will provide U.S. assistance and leadership as the Office Director from his home base in the Los Angeles Office. Although Degenkolb Mexico is new in name, its vision began to form with Jose nearly a decade ago.

Jose is a structural engineer with deep roots in Mexico as well as Degenkolb. After earning his undergraduate degree at a university in Mexico City, he then received his master’s degree in New Zealand at the University of Canterbury. He started working as a structural engineer in Mexico City and onward to Southern California before joining the Degenkolb San Francisco office in 2010. During that time, he worked heavily with San Francisco Principal, Kirk Johnston, on a variety of projects. “I learned a lot during that period with Degenkolb. They were the most formative years of my career.” In 2014, he decided it was time to relocate back to Mexico.

“However, I didn’t leave Degenkolb altogether.” Leveraging his academic and personal background, he returned to his birth country to provide a unique service that not many were qualified to do as a licensed structural engineer with diverse experience abroad. He continued working on retainer with Degenkolb in Puerto Vallarta until he finally settled down in San José del Cabo.

It was there that he founded his own company called Seis-Mex (Structural Engineering Integrative Services Mexico). As Jose was setting up his company, its partnership with Degenkolb influenced its trajectory. “I’ve been modeling the company based on the principles of Degenkolb, keeping the quality of our work and the respect for our employees and clients as a top priority. The wellbeing of all who collaborate with us is reflected directly in the quality of the services we provide.” Seis-Mex operated successfully in Mexico, keeping a close collaboration with Degenkolb through Jose’s work until a large confidential project in Cabo with highly demanding technical skills and an aggressive schedule catalyzed the merger—thus creating Degenkolb Mexico.

Degenkolbers from the Mexico and Los Angeles offices with Mexico Office Director, Daniel Zepeda, and Associate Principal and Engineer Manager, Jose Antonio Flores Ruiz, in Mexico.

The new office offers U.S. and Mexico-based clients a unique capability through a fully staffed and operating Mexico office that can service projects based in Mexico and other parts of Latin America. Additionally, there is growth potential and a diversification to Degenkolb’s book of clients by expanding the firm’s market and the impact of its engineering services across borders—bringing state-of-the-art structural and seismic engineering design practices to Mexico. Located in San José del Cabo, the office is easily accessible to all the Degenkolb offices with direct flights to other cities.

Jose remarks that he is proud of the opportunities being offered to the talented engineers in his country through Degenkolb. “The engineering opportunities that Degenkolb Mexico is providing to our local engineers don’t come easy in Mexico.”

With the creation of Degenkolb Mexico, the office can become one of the top regional firms by offering our employees competitive benefits, compensation, and career growth opportunities not commonly found in the broader Mexican structural engineering community.

Stacy Bartoletti, CEO and Chair of Degenkolb Engineers, commented: “We are very happy to have Jose and his full team join the Degenkolb family. We have maintained a strong relationship with Jose for many years and this transition is long overdue. Our clients with operations in Mexico and Latin American can now rely on Degenkolb to provide our strong level of excellence and service to their local projects.”

Daniel Zepeda, Principal in Degenkolb’s Los Angeles office and Mexico Office Director, added: “It is definitely an exciting time at Degenkolb. We have a team of highly qualified Mexico engineers that will work hand in hand with our U.S. team to bring our high-end structural engineering expertise to our Mexico and Latin American clients.”

Daniel Zepeda serves as the Mexico Office Director and liaison between Los Angeles, the wider firm, and Degenkolb Mexico. Jose serves as Associate Principal and Engineering Manager working on-the-ground to establish the Degenkolb Mexico relationships with clients.

If you’d like to learn more about Degenkolb Mexico, please reach out to Daniel Zepeda or Jose Antonio Flores Ruiz. We are excited with this opportunity, and we hope that you are too.

Contact Us

Daniel Zepeda | Mexico Office Director and Principal | dzepeda@degenkolb.com | 213.596.5000 (ext. 5014)

Jose Antonio Flores Ruiz | Associate Principal and Engineering Manager | jfruiz@degenkolb.com | 213.596.5961

Mexico Team Two Day 3: Jojutla de Juárez, Morelos

The team departed our hotel at about 8:30 Saturday morning and headed south about 90 miles to Jojutla de Juárez. The highway climbed to over 10,000 feet above sea level as we left Mexico City. The view from the top of the mountains surrounding the city gave us a real appreciation for the basin that Mexico City is located in.

Jojutla is the municipal seat of the State of Morelos and has a population of approximately 50,000. Jojutla is located on a relatively flat plane next to the Rio Apatlaco, which makes it an ideal location for farming and raising livestock, which are the primary industries in the area.

The earthquake caused wide spread damage to Jojutla, which is located only 45 miles from the epicenter of the earthquake. Many of the buildings in the central business district were heavily damaged, with partial and total collapses. The primary building type we observed was nonductile concrete with masonry infill, which is the standard type of construction for much of the area. There were whole blocks cordoned off, and demolition and clean-up operations were still under way. On some streets, building owners were already making repairs to buildings that had only minor damage. Unfortunately, the same construction materials and techniques were being used.

The local officials, or delegation as building owners were calling them, had taken to tagging buildings by spray painting green, yellow or red dots on the front of the buildings. We ran into a group from the government that was going back around to all the buildings that were tagged and noting their address.

While many of the streets and shops were closed, just one or two blocks over it was business as usual at the two main markets in town. We even noticed that stores were operating in buildings that were yellow tagged and that some business owners were inside their red-tagged buildings. While there were many police and soldiers from the national guard in the area, there was no one keeping people out of the closed off areas. It appeared to us that those who were inside their condemned buildings were concerned about theft of their shop inventory. In the building pictured below, which suffered a partial collapse, the business owner had crews inside and on top of the building removing their business inventory before the government was going to demolish the building. Similar to Mexico City, the communication from the government was vague, as the owners of this building did not know how long they had to clear it out.

One other interesting building we viewed was the main cellular phone network exchange for Telmex. The building was partially collapsed and, according to the security guard stationed out front, was still shifting. The building amazingly still had power and was operating and an emergency generator had been brought in just in case power was lost. However, no one was willing to go inside if needed to transfer power over to the generator or to perform any maintenance on the network equipment. The guard indicated that this was a major exchange for the whole state of Morelos and that if it went down, cell phone service would be lost over a large part of the state. Telmex was working to transfer the network traffic to other locations, but still needed the building to operate until the transfers were complete. With out this vital communications link, the city and people of Jojutla would have been even more cutoff from the outside.

After viewing the scope of destruction that the earthquake inflicted on the town, it is clear that the recovery process will be slow and expensive. While the type of damage that we observed in Jojutla was typical of the style of construction, the trip reinforced several ideas about the importance of resilience, especially the need to get people back to their normal daily lives and planning for disaster response. Finally, the most important and pressing need, one which has been identified in past earthquakes, is the need for improved earthquake-resistant designs using locally available materials and methods.

As we headed back to Mexico City, we stopped on the southern edge of town to observe a building that had sustained a partially collapsed floor. The building was a nine-story reinforced concrete building, that was previously seismically strengthened by jacketing of the concrete columns with steel angles and plates. However, we noticed that the floor that sustained a partial collapse did not have strengthened columns. Upon closer inspection it was observed that the strengthening of the columns was not uniform or regular throughout the building. We guessed that perhaps only the columns that were damaged during the 1985 earthquake received the column jacketing.

This building again reinforces the need to be constantly improving seismic evaluation and upgrade techniques and the need for regulations to address existing buildings that pose a danger to the public. There are many nonductile concrete buildings scattered all over California. This earthquake once again highlights the need to address these types of structures before a similar disaster occurs in California.

Life Returning to Normal in Mexico City

It almost goes without saying that Mexico City is huge. We’ve also found it largely undamaged, even in the immediate vicinity of collapsed buildings. The loss of life is tragic and perhaps could have been avoided, but overall we’ve seen a city returned to life two weeks after the earthquake.

Operation Hospital, undamaged

We spent Day 2 visiting hospitals to set followup appointments and walking some of the neighborhoods that have received the most media attention — Roma and La Condesa. While these neighborhoods are clearly more affluent than the middle-class neighborhoods we visited on Day 1, the patterns of damage are similar. The most widespread damage is nonstructural — cracking and spalling of plaster and glazing. These create falling hazards but in many cases the building structure is intact. In some cases it appears that buildings have been evacuated and closed due to nonstructural damage.

Nonstructural facade and glazing damage

Unlike the experience in Christchurch where much of the central business district was shut for months, the street closures for damaged and collapsed buildings are in residential neighborhoods and the closures are much smaller: the space in front of a specific building or a few blocks at most. Many of the closures around collapsed buildings have homemade signs requesting no photos be taken out of respect for the victims. Every neighborhood we’ve walked through also has many signs for meeting places and for places where help is offered.

Mid-rise masonry infill buildings have gotten much of the attention since they sustained the most damage, but there are also many concrete wall buildings, steel moment frames, and steel braced frames, particularly for newer buildings. The concrete walls can be massive, and in the buildings under construction appear to be heavily reinforced with boundary reinforcement and closely-spaced ties. In many of the steel frame buildings, each bay has bolted end plate moment connections, somewhat similar to older US construction with more distributed frames. Construction here is built for strength, and we understand that this is reflected in the building code with relatively low ductility factors.

Steel moment frame parking garage without observed damage

SAGARPA building with concrete walls and braced frames

Given this construction, many buildings likely have more strength than required by code, so the vulnerabilities come from irregularities rather than a lack of strength or ductility. But we have also seen many buildings that would not pass ASCE 41 checks that performed well. Whether due to internal frames that may not be visible from the street, vagaries of soil and ground motion, or other factors is difficult to say.

Concrete frame across corner from similar damaged building

Wall building with concrete braced frames

Based on the ground motion data, this was a design-basis event for many parts of the city, particularly in the transition zone from lakebed to firmer soils. While the construction types and soil amplification issues are different, the amount of damage is not terribly different from what we might expect in the US in a design-basis event. Our codes may allow even more damage at the design basis ground motions albeit with the intention of preventing fatalities. However, just as in Mexico City we have a building stock that of varying eras of construction and quality. We know that many types of these existing buildings are vulnerable to earthquakes, particularly the older masonry and non ductile concrete buildings that are similar to the construction in Mexico City.

Degenkolb’s second team of engineers lands in Mexico

Following in the footsteps of Team 1 we started our day with a visit to the Colegio De Ingenieros Civiles De Mexico (or CICM) to get badges and a list of buildings to help review in greater depth after initial evaluations done previously. We then headed out to the Tlalpan and Coapa neighborhoods. At our first stop, we learned just how valuable the CICM badges were as we needed them to convince police and others to allow us into the cordoned off areas. The first building was a 5 story 40 unit apartment building with three separate ‘wings’ above the first elevated level. The storefronts on the street side have been closed since the building was tagged and we were approached by a shop owner who was hopeful we were the people who were finally here to let her back in to recover her goods. She was understanding, albeit disappointed, to learn that we were just the next to help get them answers but not the ones to make the final call.

This was our first direct exposure to a building with significant damage of transverse masonry infill walls, but was not our last.

Our next stop took us to an area with one street which was hit hard. There were 5 buildings for us to help assess on Hacienda de la Escalera. All of them fit our typical profile of 5 story apartment buildings with masonry infill walls above the first elevated floor and a soft story with columns or significantly less walls at the ground level.

Some are smaller buildings located mid-block with visibly less damage.

And in some were larger and located at corners with no adjacent structures.

With difficulties getting into buildings, the highlight of our day was by far Escalera 68. The building was not restricted in use, but from our initial exterior assessment, it was heavily damaged.

A sign taped to the wall notified readers that apartment 301 was home, so we took a chance and rang the box. The resident was home, spoke English and was more than happy to let us in the building and show us around some of the apartments & the roof.

We noticed the building was tied together very uniquely and that it appeared to have a true concrete frame structure, different from others we saw which had bearing unreinforced masonry.

These suspicions were confirmed with the type of damage we saw upstairs.

And when we got upstairs she even had the construction documents from 1979!

On our view at the roof our lovely host requested a picture with her husband and son and we were more than happy to pose with them!

We look forward to taking what we saw and using the drawings to better understand this unique building. Day one is in the books and tomorrow we’re going to seek out more buildings to learn from.

Pictures coming from Mexico continue to show damage throughout the city

Damage to glazing and infill masonry at a church structure.

Existing hospital building with an exterior steel buttress retrofit. Vertical steel plates are used as a seismic “fuse” to help dissipate energy. From the outside, no damage was observed.

Connecting bridge between a parking structure and a hospital building is supported with temporary shores, due to damage at the connections.

Taller structure to the left has pounded with the one-story structure on the right, resulting in diagonal shear cracks through the front wall of the one-story structure.

Members of the Degenkolb Team and a local architect, observing one of the historic buildings designed by the famous architect V. Kaspe F. Tribouillier.

The twin buildings –These buildings were essentially built as “twins”; however, after the 1985 earthquake they both sustained heavy damage. The building on the left had the upper 4 stories removed as part of the retrofit; and its twin on the right was retrofit with interior steel braces (based on conversations with the owner)

Photo shows the common practice of using diagonal concrete braces, with infill masonry. Note that some of the concrete columns have been retrofit with steel plate and angle jackets.

Known as the “Durango Building”, this structure was Retrofit prior to the 1985 earthquake (via the exterior steel braces and columns). We understand that it was not damaged in the 1985 earthquake, and from our exterior observations, we did not see any damage due to this earthquake.

Degenkolb Engineers, Wayne Low and Robert Graff take notes regarding the structural retrofit scheme used at the “Durango Building”

Ceiling damage at a seismic joint. Floors and wall framing utilized seismic joint detailing; however the ceiling did not.

Damage to an interior stair support connection.

Partial collapse of a hard lid ceiling at a large interior space. Ceiling was framed via hat channels and C-channels; however, no seismic bracing wires or compression struts were utilized.

One of the few distribution system failures observed by the team. The disconnection of a roof drain pipe at a joint. Resulted in rainwater entering the space.

“Anchored” file cabinets leaning precariously over. Cabinets were anchored to the infill masonry walls with only drywall screws.

Un-anchored Compressed air tank did not show signs of sliding or movement.

Un-anchored DA tank did not show signs of sliding or movement.

Temporary shoring supports used at the first level of a multistory condominium building. Although damage to the exterior of the building could not be observed, one column at the lowest level had experience structural damage.

Multi-story concrete frame building retrofit with steel braced frames. No damage to the structure could be observed from the exterior.

Mexico City Team Visits a Damaged Hospital

To learn from EQs, Degenkolb visited a damaged hospital located in Mexico City. The hospital was closed after the earthquake and the patients evacuated within an hour of the event. Built approximately 40 years ago and prior to the 1985 earthquake, the concrete wall structure handled the earthquake well, with limited damage. Often, the operation of a hospital can hinge on how its non-structural systems perform.

The hospital sustained damage to its brick interior walls and stairwells. The elevators used to transport patients were damaged and unusable. Made up of multiple buildings, we saw damage at expansion joints from pounding in the EQ. In the lobby of the ED, the hospital sustained damage to its ceilings and a break in a roof drainage pipe, leading to water in the hospital.

Examining systems in the central plant of the hospital we noticed that only limited pieces of the mechanical, electrical, and plumbing equipment were seismically braced, but did not have any damage. Piping systems within the central plant were also undamaged. Could the hospital have had more damage if the event had been bigger or the earthquake shaking different? The Hospital will be closed for the next 12 months as they repair and return the facility to operation.

Non-structural Damage Views in Mexico City

The Degenkolb team continues to explore the streets of Mexico City. We have seen buildings that do not have damage to the main columns, beams or bearing walls, but that does not mean there is no damage. Often the damaged are found in the non-structural systems like the exterior.

Many Mexican buildings have damage in the brick infill and partition walls between concrete columns. Often the plaster on the face of the walls can be found on the streets; delaminated from the brick or concrete on the exterior. Even for new building, we observed part of the exterior’s wall brick veneer collapsed on the sidewalk, leading to concern by the building occupants. Often perception is worse than reality. Could these failures have been prevented by using better anchors or adhesive? Should these building materials be avoided on exterior walls when they present a falling hazard for people around the building?

Even when the exterior is more like what is found in the US, there can be damage. Below shows a collapsed storefront in Colonia Copa. Anchors used to attach to the concrete slab were very small and over 60% of the anchors slipped out of the concrete holes instead of breaking the concrete. Could this have been avoided with better installation and inspection?

Day 3 Mexico City: Col de Valle Central and La Condessa districts

Continuing our reconnaissance, Degenkolb visited the Col de Valle Central and La Condessa districts. As we have seen more buildings, we are starting to see some typical patterns in the damage and that building placement may affect the building performance. Similar to older houses in San Francisco, residential building in Mexico City are often built shoulder to shoulder to each other, with little or no gap. Although we think of pounding between buildings as being bad, there might be an unexpected benefit. Could one building prop up another and slow or stop the building from moving in an earthquake, even if it has a weakness like a soft story? When a building is located on a corner, Mexican buildings typically have solid walls on the back two side and storefronts along the two street sides, which would lead to unbalanced, twisting of the building in an earthquake. Could this be why many of the heavily damaged and collapsed buildings are located on the corner of the street? The photos here shows the damage to a corner buildings with the damaged concentrated on the open sides of the building.