On the morning of February 28, 2001, moments before 10:54 a.m., Lisette Terry (Degenkolb Associate) had just stepped out of the shower in her apartment before class at the University of Washington. “I noticed my kitchen ceiling was bouncing, and shortly after I felt the floor start moving like the entire building was waving on fluid. The way the structure swayed—it felt like I was riding a surfboard.”

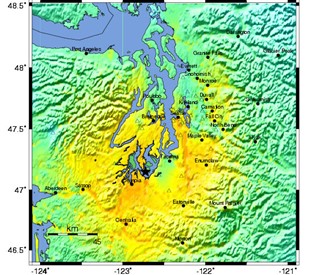

What she was experiencing would come to be known as the Nisqually earthquake, a 6.8 moment magnitude event that began 35 miles underneath southern Puget Sound as the Juan de Fuca Plate sank further into the Earth’s mantle. The quake’s epicenter was northeast of Olympia, Washington, near the Nisqually Delta—its namesake—and was felt as far north as Vancouver, B.C. and east as Salt Lake City. In a matter of 40 seconds, the quake injured hundreds of people, killed one, and caused an estimated $2 billion in property damage.

The star marks the epicenter of the Nisqually earthquake in February 2001.

Nisqually’s Impact on Degenkolb

Nisqually may have lasted for less than a minute, but its effects forever altered Washington State’s seismic response and Degenkolb’s trajectory in the Pacific Northwest region. “Nisqually was the impetus behind the founding of Degenkolb’s Seattle office,” recalls Stacy Bartoletti (Degenkolb CEO). He remembered feeling the quake’s shaking from 145 miles away in Portland at Degenkolb’s 12th-floor office that February morning 20 years ago. Stacy connected shortly after with Travelers due to the firm’s prior collaboration with the insurance company following the 1994 Northridge quake. Throughout that year, he and other Degenkolb project managers began traveling back and forth to Seattle, working on a range of projects with Travelers, including assessing post-earthquake damage to clients’ buildings and other related claims work. Some of this work featured the hard-hit Old Town—also known as Pioneer Square—in downtown Seattle with its historic unreinforced masonry (URM) buildings that bore the brunt of the temblor’s damage.

“There was a lot of professional activity work after the quake centered around looking at various scenarios and expanding seismic awareness on a state-wide level,” recalls Stacy. Degenkolb has been involved since the inception of these efforts, helping guide the state and community to become more resilient for the next quake. Cale Ash (Degenkolb Principal) joined the Degenkolb Seattle office in 2003 as its first Designer. He quickly became involved in the ongoing seismic efforts and projects of the firm, including the Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup (CREW) and the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute’s (EERI) Seattle Fault Scenario: a document that “communicates the impact of a quake to a wider audience so it can be used for future preparation,” he describes. “I saw that as a valuable way to get further involved in earthquake risk-reduction activities.” Many others in the Seattle office and beyond have since followed suit, including Kyle Steuck (Degenkolb Associate Principal) whose interest in seismic hazard and loss analysis led to his involvement with EERI. He has gone on to serve as the President of the Washington State chapter.

The current Seattle Office lobby.

Seismic Resilience in Washington State

Nearly a decade after Nisqually, the state rejuvenated the Washington Seismic Safety Committee (WSSC). As part of the WSSC, Degenkolb played a significant role in developing Resilient Washington State—a policy and planning document published in November 2012 by a subcommittee that Stacy chaired. Resilient Washington State strived to quantify the state’s seismic risk and the impact on its systems if another damaging earthquake occurred. This marked the beginning of a line of work meant to facilitate state-level implementation of seismic risk reduction over a 50-year period. With eight years under its belt, Stacy notes that “there is work being done but the Initiative is relatively in its infancy.”

Part of that continuing work towards seismic risk reduction includes seismic upgrades. “The Nisqually quake made many recognize the hazard and take action,” notes Stacy. Two decades later, URM structures—like those damaged in Seattle’s Pioneer Square—remain standing with many still awaiting retrofits. Despite the known risk of URM structures, Stacy notes that it has taken decades to deal with URM buildings due to the required “wherewithal” among stakeholders to make it possible and the sheer number of outstanding structures. Cale adds: “Earthquake risk reduction is not solely an engineering endeavor. It needs to involve community to be effective.” He cites the technical requirements of the proposed City of Seattle’s URM Ordinance and how officials had trouble gaining public support for more than 10 years around retrofit mandates before it was passed. “We have helped our clients understand these requirements—that they are likely to come into play at some point—and we’ve advised them as they consider proactively retrofitting their buildings,” he adds.

Some of these outstanding URM buildings happen to be schools which originally opened before this construction type was phased out in the mid-1950s and which pose a risk for Washingtonian students. Degenkolb’s involvement with the Washington State School Seismic Retrofit Pilot Project through the WSSC sought to find methods for assessing the earthquake performance of schools and offer recommendations for future actions. Lisette (Degenkolb Associate) knows the risk all too well. Her daughter currently attends one of the older URM schools that is slated to be seismically retrofitted in 2024. “Her school is more than 100 years old. I read a structural engineer’s assessment of the building before she went to kindergarten there and the findings were not good.” Cale recognizes that Nisqually launched an unprecedented amount of seismic work but knows that there is still much work to be done for seismic safety of schools and other URM structures statewide. The advocacy and research efforts that Degenkolb has participated in through the WSSC and beyond have helped galvanize support and promote understanding of Washington’s seismic risk.

Example of a URM building damaged by Nisqually.

Seattle’s Seismic Risk

Beyond schools, the seismic resilience of hospitals and other healthcare facilities remains a significant concern. Mike Bramhall (Degenkolb Principal) recalls being summoned to Harborview Medical Center— the designated disaster control hospital for Seattle and King County—a few hours after Nisqually hit. He was one of the few engineers available to travel to the hospital to conduct a rapid assessment of any damage. In the seven hours he spent on site, Mike “can distinctly remember a seismic joint on the fourth floor [of one of the buildings]. The building moved enough that it damaged the cover, so you could look inside the joint and see the blue sky through it.” Despite the structural damage, he was able to give the hospital the go-ahead to remain in operation—welcome news to the many of injured from Nisqually who were transported there for treatment.

Mike reflects on his concerns around the effect a larger quake may have not only on Seattle’s medical response to a disaster but the bustling city’s infrastructure. “Seattle is unique in that it’s very linear. The north part of Seattle is cut off from downtown and the south side by lakes and bridges. If one of the bridges goes down, you must drive around 80 miles to get from one side of the city to another. If a quake damages the I-5 Ship Canal Bridge you almost effectively cut off all traffic of goods and services going north. Other cities have that but not to the degree that Seattle does.” In other words, seismic resilience translates to economic resilience. Lisette reflects on the now defunct Alaskan Way Viaduct, a roadway that eventually was torn down due to deficiencies illuminated by Nisqually and a notorious predecessor— the Loma Prieta earthquake. “I thought about seismic risk a lot when I used to drive on the viaduct [before it was demolished]. I had a fear of being pancaked,” says Lisette.

Downtown Seattle looking towards Mt. Rainier.

Looking Forward

“Nisqually was an eye-opening time for the region and for Washington State to do more to mitigate the earthquake hazard,” notes Stacy. David Sommer (Degenkolb Associate) reflects on Nisqually’s legacy and how much of the work and effort being performed is geared toward another looming threat: The Big One. “People around here don’t realize that Nisqually was not a large quake, so trying to educate our clients about what the Cascadia Subduction Zone could do to the area can be a struggle. People remember some chimneys falling after Nisqually and believe that ‘we’re going to be okay.’ However, the Cascadia Subduction Zone and Seattle Fault scenarios could literally change the landscape of Seattle.”

Many in the earthquake community face the same challenge. “While Nisqually is a good reminder that we are in a seismically active area, there are bigger earthquakes we need to keep in mind and address,” cautions Cale. “Nisqually is the type of earthquake we can expect to see every 30 to 50 years whereas larger events that we are trying to prepare for are what we expect to see every 300 to 500 years. It’s now been roughly 320 years since the last Cascadia Subduction Zone event, so we’re in the potential ‘sweet spot’ geologically.” Stacy adds: “Seismicity and seismic risk are well known in the Pacific Northwest now. There is a tremendous amount of work that needs to continue to happen or ramp up.” Degenkolb remains active in building seismic resiliency alongside our peers thanks to the heightened awareness generated by Nisqually two decades ago.