ARE WE READY FOR THE NEXT ONE?

By Daniel Zepeda, S.E. and Matt Barnard, S.E.

(Updated January 17, 2019)

Soft-story apartment buildings affected by the quake. Link.

(Photos by Degenkolb Engineers)

On January 17, 1994 a magnitude 6.7 earthquake hit Southern California. The ground shook rigorously for approximately 15 seconds, 20 miles from the Los Angeles downtown area. When the shaking stopped, the earthquake had left thousands injured, and tens of thousands without shelter, and claimed the lives of 57 people. Sixteen of those deaths happened in the Northridge Meadows Apartment buildings which contained a structural deficiency known as “Soft Story.” Many buildings and bridges collapsed, roads were closed, hospitals were damaged, and emergency departments were called to action. It is estimated that the Los Angeles area suffered more than $40 billion dollars in economic loss due to the earthquake. At the time, it was one of the largest economic losses caused by a natural disaster in US history. However, despite all these losses WE WERE LUCKY! According to the FEMA FA-163c report, “Many experts believe that because the earthquake occurred on a holiday morning, casualties were significantly lower than they would have been if the quake had happened at any other time.” The earthquake is not considered “The Big One.” Today marks the 25th anniversary of this massive event and we cannot help but ask ourselves, Are We Ready for the Next One?

To answer this question we can examine what we have accomplished in the last 25 years to reduce our seismic risk in California:

Hospitals

Medical facility in the Northridge Reseda area.

(Photo by Degenkolb Engineers)

The 1994 earthquake damaged many hospital buildings that serve critical care functions. As a result, many of the victims had to be transported longer distances to get proper medical attention. Senate Bill 1953 was signed into law, as an amendment to the Alfred E. Alquist Hospital Seismic Safety Act. The bill, addressed the functionality of structural and non-structural components after a major earthquake. It applied to all general acute care Hospital buildings in California.

The bill mandated that hospital buildings are categorized into Structural and Non-Structural Performance Categories (SPC and NPC) based on their risk level. Depending on that risk level, the bill allotted specific time periods for the buildings to be evaluated, retrofitted, decommissioned or replaced.

New Retrofit Column for Retrofit of the Northridge

Medical Center Diagnostic and Treatment Building

(Photo by Degenkolb Engineers, Structural Engineer

of Record and Prime Consultant)

The program has evolved over the years to allow additional time to evaluate and retrofit the most difficult buildings. From 2001 to 2017, OSHPD reported that the quantity of SPC 1 (Collapse Hazard) buildings decreased from about 1000 buildings to about 220 buildings (80% reduction). Despite the success thus far, the program continues to evolve and is expected to be completed by the year 2030.

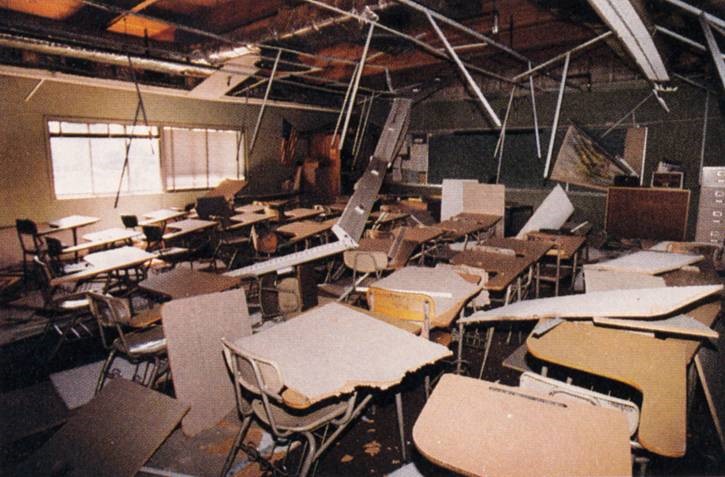

Public Schools

Classroom Damage after the 1994 Northridge Earthquake. Link.

Much like the hospitals, schools were deeply affected after the 1994 Northridge Earthquake. This caused great concern among our communities given that our schools house our children for about 8 hours a day. We envision schools as places that could provide temporary shelter for those who had lost their homes in the event. As such, Assembly Bill 300 was enacted in 1999 requiring the Department of General Services to survey the older California K-12 School buildings designed before the 1976 CBC went into effect. Surveyed buildings were divided into categories depending on their expected performance in a seismic event.

Findings were presented without specific school names or sites, but included an analysis of the overall results. The report was released in 2002. In 2003, The Division of the State Architect (DSA) contacted each of the school districts and indicated that survey data pertaining to that district was available upon request. It also stressed that the inclusion of buildings in the inventory would require further structural evaluation by a structural engineer to determine if retrofit would be required.

Seismic Strengthening of Existing Plywood Shear

Wall at Shearman Oaks Elementary School

(Photo by Degenkolb Engineers, Structural Engineer of Record)

In 2008, DSA contacted the districts requesting information on qualifying buildings that may have been missed by the original survey. Per requests from the public, and in compliance with the Public Records Act, the entire AB 300 survey became public information. Unfortunately, due to lack of funding, full building evaluations and retrofits have not been required since the survey was conducted. However, the bill did serve to alert parents and the community of the seismic risk to our children. In addition, any major alteration to a public school building must consider its effects on the seismic performance of the building.

Private Schools

Voluntary Seismic Strengthening of Existing

Building at Willows Community School

(Photo by Degenkolb Engineers, Structural Engineer of Record)

It is noted that AB 300 does not cover private schools. To our knowledge, no major Southern California local jurisdictions have currently adopted seismic ordinances specifically targeting privately owned schools. The only ordinance by a major jurisdiction to address this issue has been by the City of San Francisco which requires an evaluation only of privately owned school buildings. Despite not having a mandatory ordinance in the books, many private schools have recognized the need to reduce their seismic risk. Many schools have voluntarily moved forward with an evaluation and retrofit of their existing buildings.

Higher Education Buildings

Colleges and universities in the State of California have recognized the imminent threat of an earthquake. They have taken big steps to reduce their seismic risk. For example, the University of California (UC) system has been evaluating and retrofitting their most vulnerable buildings since the 1970s and the adoption of the first UC Seismic Safety Policy. The most seismically vulnerable UC buildings are required to be retrofitted or removed from service by 2030. Many other buildings fall under the local URM ordinances. Another notable program is the California State University (CSU) Seismic Review Board established in 1992 to develop a retrofit program to assess their seismic risk. According to the 2002 Seismic Safety Inventory of California Public Schools report, over 145 CSU facilities that required evaluation and possible retrofits are well underway in design and construction. The California Community Colleges developed a program in 1996 to survey their building stock to better understand their seismic risk.

It is noted that private universities and colleges typically fall under local city jurisdictions. They are not held to the same requirements or processes required of the State of California colleges and universities. Fortunately, some have taken a voluntary approach to assessing and then addressing their seismic risk including completing various seismic retrofits.

Government Buildings

Private Owned Buildings City of Santa Monica

City Hall has been Seismically Retrofitted

(Photo by Degenkolb Engineers, Structural Engineer of Record)

We have all heard the heroic tales of the fire fighters and rescue teams that immediately responded to the Northridge Earthquake. We do not, however, often think about the buildings these individuals work in. If a fire station collapsed on top of a fire truck, it would be difficult for the fire fighters to respond to an emergency. If a police station collapses, they could not keep order during the chaotic moments after the event. If government office buildings fell, we could not communicate with outside municipalities to ask for help. Fortunately, there were no significant collapses of these types of buildings during the Northridge Earthquake, but it did serve as a warning sign. Many jurisdictions have identified their most vulnerable buildings and have seismically upgraded them. These include fire stations, police stations, city halls and command centers. The amount of work done to date varies depending on the institution and funding. The federal government for example has prioritized hospitals that are under their jurisdiction while some cities have prioritized fire stations, police stations and city halls. In 2016, the White House issued the “Executive Order: Establishing a Federal Earthquake Risk Management Standard” which is a great step forward in establishing our seismic safety.

Infrastructure

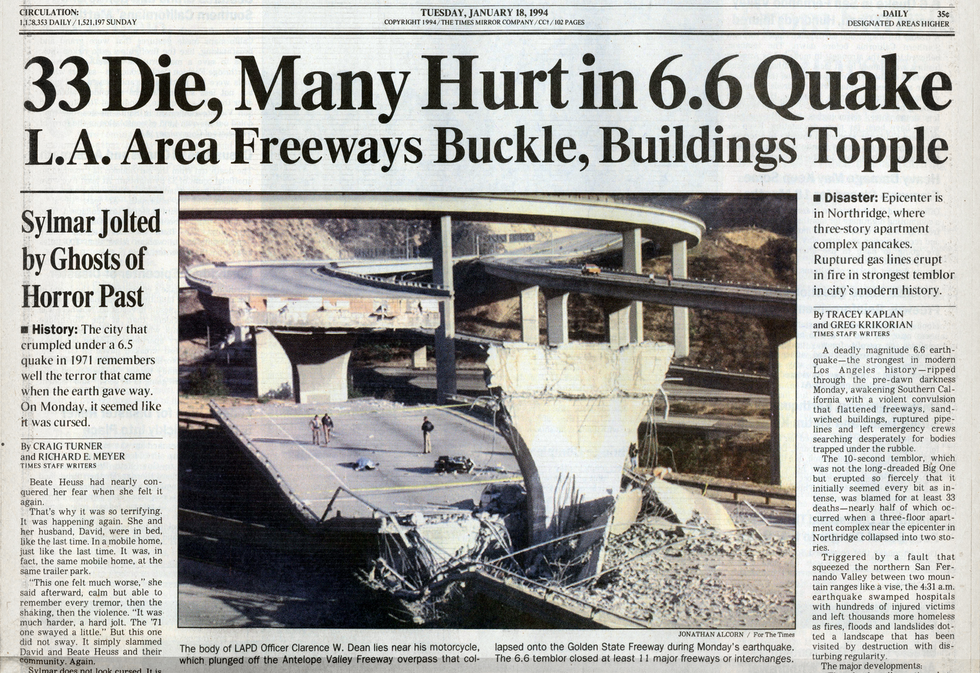

LA Times News article of the Northridge Earthquake

the day after the event

A significant problem that many of us have forgotten is the impact that an earthquake will have on our utilities. Imagine living in a house with no internet, phone, natural gas, electricity, or water. Even if you wanted to leave, the roads would be closed due to buckling, collapse and other severe damage. During the 1994 Northridge Earthquake millions of people lost at least some of their most critical utilities. According to an article published by the New York Times the day after the earthquake, over two million people were left without power for several hours, fires broke out from 142 gas main splits and phone lines were limited to emergency calls. Four major freeways in the Los Angeles area were damaged creating gridlock throughout the region.

MWD Building Evaluated for Seismic Safety

(Photo by Brett Drury, Architectural Photography Inc.)

After the quake, CalTrans put together a very extensive program to strengthen all of its bridges across the state. According to the California Department of Transportation all of the work has been essentially completed. City utilities on the other hand are still hard at work upgrading their infrastructure. Most utility companies have been performing upgrades on a voluntary basis since there are no state mandates.

Local Communities

Limited Seismic Strengthening of Existing URM

Building at Santa Fe Depot Train Station

(Photo by Degenkolb Engineers, Structural Engineer of Record)

Unreinforced Masonry Buildings

Considered one of the most seismically vulnerable building types, unreinforced masonry (URM) buildings have suffered major damage in every earthquake since the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. The State of California first addressed these buildings with the 1986 Senate Bill 547. This law required cities and counties within California’s Seismic Hazard Zone 4 prepare a survey of all URM buildings and develop risk reduction programs by 1990. Many cities including The City Los Angeles passed and enforced mandatory seismic ordinances for these types of buildings. For financial reasons, the ordinance targeted a “reasonable level of safety”. In 1994, the Northridge Earthquake tested many of the URM buildings that had been previously retrofitted. In general, the retrofitted buildings performed as expected, but unfortunately according to FEMA P-774 “… building owners often did not understand that “hazard reduction” could be compatible with a level of damage that required expensive repairs.” In 2006, the California Seismic Safety Commission reported 75% of the affected jurisdictions had implemented a mandatory seismic reduction program. It is worth noting that not all cities had the same enforcement or the same level of retrofit requirements. The legislation only mandated a survey and left each jurisdiction to decide the type and level of seismic loss reduction program. As such, there is a large variation of scope and design methodologies for the retrofit of URMs across the state.

Survey of Seismically Vulnerable Buildings

(Photo by Degenkolb Engineers, City Consultant)

Mandatory Local Seismic Ordinances

Despite the damage that occurred due to the 1994 Northridge Earthquake, it has been difficult for local jurisdictions to develop, pass, and successfully enforce seismic mitigation programs. This is mainly due to the economic pressures that a city and its residents will endure because of these types of programs. In recent years, some California cities have made seismic mitigation programs a priority and have been proactive in developing and enforcing mandatory seismic ordinances. The scope and details of the ordinances vary from city to city but the primary focus of the most recent ordinances has been targeting soft, weak, or open front wood frame buildings (SWOF), non-ductile concrete buildings (NDC), and pre-Northridge steel moment frame buildings (PNMF).

The tables below provide a summary of the cities that are actively enforcing seismic ordinances:

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

| Jurisdiction | No. of Affected Buildings |

Ordinance | Ordinance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beverly Hills | 300 Reported | Wood Soft-Story built prior to 1978 |

Approved and in effect |

| Los Angeles | 13,500 Reported | Wood Soft-Story 4 units or more built prior to 1978 |

Approved and in effect |

| 1,500 Reported | Non-Ductile Concrete built prior to 1977 |

Approved and in effect | |

| Santa Monica | 209 Reported |

URM built |

Approved and in effect |

| 34 Reported | Conc/CMU with Flex Diaph. Built prior to 1994 |

Approved and in effect | |

| 1,573 Reported | Wood Soft-Story built prior to 1978 |

Approved and in effect | |

| 66 Reported | Non-Ductile Concrete built prior to 1977 |

Approved and in effect | |

| 80 Reported | Pre-Northridge Steel Moment Frames built prior to 1995 |

Approved and in effect | |

| West Hollywood | 780 Reported | Wood Soft-Story built prior to 1978 |

Approved and in effect |

| 55 + (60 potential steel or concrete) Reported |

Non-Ductile Concrete built prior to 1977 |

Approved and in effect | |

| 31 + (60 potential steel or concrete) Reported |

Pre-Northridge Steel Moment Frames built prior to 1995 |

Approved and in effect | |

| Pasadena | 500 Reported | Wood Soft-Story built prior to 1978 |

In Development |

NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

| Jurisdiction | No. of Affected Buildings |

Ordinance | Ordinance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alameda | 100 Reported | Wood Soft-Story 5 units or more built prior to 1985 |

Approved and in effect |

| Berkeley | 327 Reported | Wood Soft-Story 5 units or more built prior to 1978 |

Approved and in effect |

| Oakland | 1,380 Reported | Wood Soft-Story 5 units or more built prior to 1991 |

Survey Complete. Retrofit voluntary. |

| Palo Alto | 294 Reported | Wood Soft-Story | In Development |

| San Francisco | 4,956 Reported | Wood Soft-Story 5 units or more built prior to 1978 |

Approved and in effect |

Concluding Efforts

Daniel Zepeda, Degenkolb Principal, with SEAOSC

Mexico City Reconnaissance Team discussing 2016

Earthquake Damage and Response

The effort to make our cities safer and more resilient after a seismic event has had great momentum over the past few years and continues to grow. Most recently, the City of Los Angeles released an earthquake early warning detection system app. The technology will provide a small amount of time that can be used to shut down rail systems, coordinate signal lights, warn emergency response teams etc.

Concluding Thoughts

SO, ARE WE READY FOR THE NEXT ONE? We hope that we have demonstrated that most jurisdictions have been taking seismic risk seriously since the 1994 Northridge Earthquake and hopefully, we are better off than 25 years ago. There is still a tremendous amount of work to be done. It is difficult to convince stakeholders and government bodies of the critical importance of these risk mitigation programs. Government entities are faced with the pressure of balancing seismic safety with the economic hardship of their communities. For this reason, even 25 years after the Northridge Earthquake we are still struggling to get most of our seismically vulnerable buildings up to a “reasonable seismic safety level.” Thousands of structures remain in need of seismic evaluation and retrofit. Unfortunately, most of us have become complacent and have forgotten the terror we feel when the earth literally moves below our feet and the devastation that comes with it. We need to let our community leaders know how important this is for the safety and well-being of their constituents as well as the resilience of our communities.

About The Authors:

Daniel Zepeda received his Master’s degree in Structural Engineering from the University of California, Berkeley and is a licensed Structural Engineer in California and a Principal with Degenkolb Engineers. With over a decade of experience in seismic evaluation and seismic strengthening of existing buildings, Daniel’s project breadth spans large medical centers, civic buildings and privately owned structures. He is the past chair of the Structural Engineers Association of California (SEAOC)’s Existing Buildings Committee and current chair of the Southern California chapter. He is currently helping cities in the Los Angeles area including the cities of Los Angeles, Santa Monica, Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Pasadena, and Culver City with their seismic programs. Daniel was a member of Degenkolb’s post-earthquake reconnaissance team that surveyed both the 2010 Chile Earthquake, the 2010 Baja California Earthquake, the 2016 Taiwan Earthquake, and the 2017 Mexico City Earthquake. He is also participating in the update of the latest version of ASCE 41 and development of the new ATC-78 and ATC-134.

Matt Barnard is a Principal in the Los Angeles office of Degenkolb Engineers. Matt has a M.S. in Structural Engineering from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and is a licensed Civil Engineer and Structural Engineer in California. His experience includes new design, alternations, tenant improvements and retrofits for healthcare, higher education, and civic facilities. Matt is a Director on the Board of the Structural Engineers Association of Southern California (SEAOSC) and represented SEAOSC on the Building Forward LA Task Force that was created by Mayor Garcetti’s Resilience office. He is a Los Angeles Affiliate Board Member and active mentor of ACE Mentoring and was named an National Outstanding Mentor in 2015. Matt is also a member of the national Guidelines Committee for the Council of American Structural Engineers, a member of the Technical Advisory Committee for the US Resiliency Council, and a past subcommittee chair for SEAOSC Buildings at Risk Summit. He is a disaster service worker volunteer through the California OES Safety Assessment Program. Matt also serves as a member of the part-time faculty for California State University, Fullerton.