80 Years of Excellence: Henry Degenkolb the Earthquake Chaser

In part 4 of our 80th Anniversary series, we talked to Paul Degenkolb, Henry’s son, about what it was like growing up with a structural engineer as a father.

Earthquake Chasing Goes South

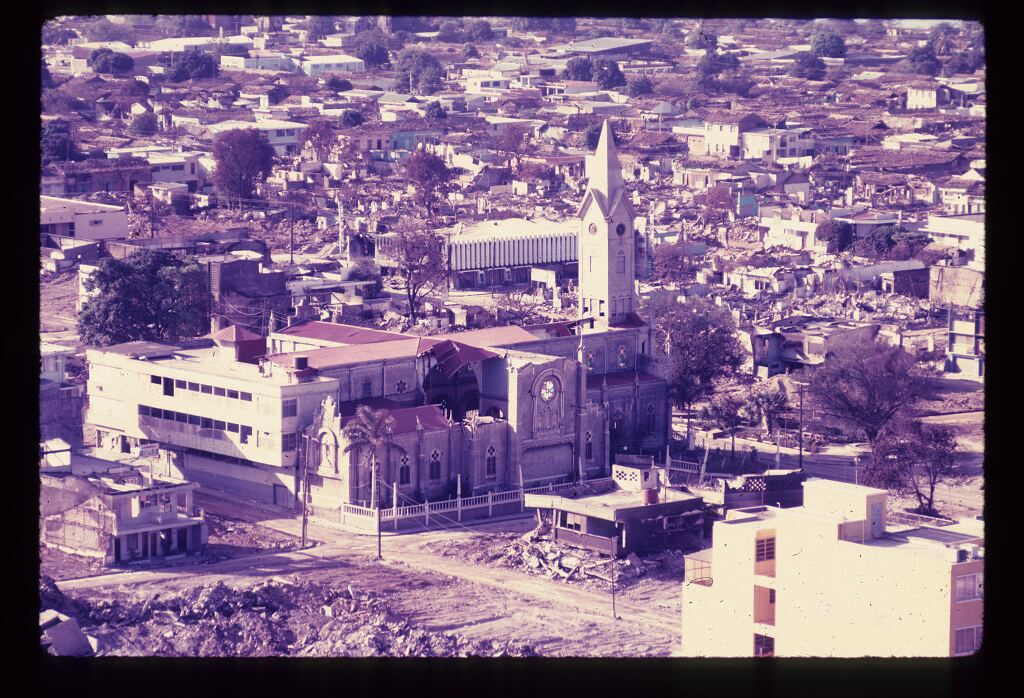

On December 23, 1972, just after midnight, an earthquake hit Managua, Nicaragua, and Henry got down there as soon as he could, bringing 19-year-old Paul along (ostensibly to carry Henry’s many cameras). Though Paul had seen the damage earthquakes wrought and had heard his father talk about it many times, he was unprepared for seeing the devastation first-hand. But he also got to see how dedicated of an investigator his father was. During the plane ride down, the pilot had to get an idea of the ground conditions before landing. He brought the Boeing 707 down to 2,000 feet and turned hard to the left, then hard to the right; with a bank angle of 60 degrees, everyone on board was experiencing about 2Gs, meaning everything felt about twice as heavy. However, throughout this plane ride, Henry was going up and down the cabin trying to find the best locations from which to shoot pictures.

Aerial view of damaged buildings.

Once on the ground, Henry’s experience as a field investigator kicked in and he hired both a driver and experienced interpreter for the duration of the stay. That first day, they visited a parking garage that had collapsed. Paul had just finished documenting the conditions inside the garage when he was approached by a tall, thin, bandana-wearing man looking like he had walked straight out of an old Western movie. The man saw the USGS sticker on Paul’s hard hat and asked his name and affiliation. When he heard Paul’s name, he asked if he was related to the Henry Degenkolb. Paul confirmed that he was Henry’s son and introduced the man to Henry. The man, Filadelfo Chamorro, was one of the most respected structural engineers in Nicaragua and was familiar with Henry and his work. Filadelfo stayed with the team for the entirety of the trip and remained in contact with Henry and other Degenkolb engineers for many more years.

Several days later, the group visited a bank that Filadelfo had been the SEOR for, the Banco de America. Filadelfo said that, although it did not meet all the US codes on paper, he’d designed it the way he thought Henry might. The building had suffered minimal damage – some spalled concrete at four doorway locations on each floor where air conditioning ducts had been passed through the beam (header), not in accordance with the design drawings. Kitty-corner to that bank was Banco Central de Nicaragua, which, despite meeting the US codes, had suffered such severe damage it had to be almost completely torn down

One of the things that made Managua different from other earthquakes was the degree to which Henry and the other team members examined the social impacts of some of the damage. In Managua, it became apparent that, in a post-disaster situation, hospitals and fire stations were critical. As Paul remembers, at that time, there were only two of each in the city; one of the fire stations collapsed on the fire engines and both hospitals were damaged to the point that they could not be used.

Henry’s Technical Competency

Aerial view damaged and minimally damaged buildings.

The trip to Managua presented an interesting juxtaposition in building design. One building, which met code on paper, failed, while the other did not. These two examples illustrate the basis of Henry’s attitude towards the code – codes are guidelines and are not a substitute for good design. Codes help institutionalize knowledge – they help people understand what works and what doesn’t work. But codes aren’t going to get an engineer to the final answer about building design, and they shouldn’t be used to justify or cover for mistakes. Henry believed it is up to the engineer to know what’s a good design and what’s a bad design. He felt strongly that a good engineer should not only be able to put together a well-designed building, but also recognize a bad design when he sees one.

Henry always emphasized the importance of understanding things in context. Though he loved what computers could do for the understanding of buildings, he took it with a guarded approach. No matter what, there needs to be a person behind the computational work, taking the time to understand what is going on and viewing the bigger picture.

As an engineer, Henry enjoyed working with people of various professions and encouraged discussion. He always assumed that whoever he was dealing with had something positive to add, and never objected to being told he was wrong if the person talking to him was able to back up their assertion. Crucially for the future of Degenkolb the company, Henry wanted his engineers to really think about what they were doing and why they were doing it that way. This is one of the strongest legacies that Paul thinks Henry has left for the company.

Henry: One of three

Managua wasn’t the only time Paul was asked if he was Henry Degenkolb’s son. A few years later, when Paul was attending City College, he’d take the Bart train to Glen Park and walked the rest of the way home. It was a long walk though, so Paul was open to hitchhiking, especially when the weather was bad. One evening, on his way home in the rain, he was picked up by a man who was involved in the construction industry. When Paul told the driver his name, the driver said “Ah! Which one do you belong to?” Henry was only one of three Degenkolb brothers; according to the man giving Paul a ride home, if you were involved in construction, you were bound to run up against one of the Degenkolb brothers. Paul’s driver had come across all three, three and began sharing what he knew about them all. John was a fire engineer and former fire chief and had develop many of the fire codes on the books today. Oris was involved in bridges and transportation as he worked for CalTrans. Anyone involved in highway construction had come across or heard of Oris. Henry was the structural guy and part of the group who verified building codes for the state. If you wanted to get something through the code, you were very likely going to come across him. Henry was well-respected and didn’t necessarily hold onto ideas simply because he’d authored them. He was always open to changing his mind if the reasons added up.