Throughout the month of April, Degenkolb is celebrating 80 years of structural engineering by taking a look back at our founder, Henry Degenkolb. We talked with people who knew and worked with him, and present those stories here. Part 1 of the 80th Anniversary series comes from James Malley’s recollections of Henry and his contributions to the field of structural engineering.

It is Henry Degenkolb, and his professional connections, who Jim Malley credits for his 37-year career at Degenkolb Engineers. In 1982, Jim was a graduate student at UC Berkeley, working with Professor Egor Popov, who was a friend and contemporary of Henry. As the semester wound down and summer was in sight, Egor informed Jim that funding had run out for his research project and he couldn’t keep him working full time during that upcoming summer. On Jim’s behalf, Egor contacted Henry, asking if Jim could intern with Degenkolb for the summer. Jim completed the internship and was asked back after graduating. He joined the firm the next year as an engineer and has stayed for the better part of three decades.

Henry was left-handed, like Jim, and was often seen with a cigar in his right hand, leaving his left hand free to hold a pencil. He was a passionate and curious engineer, and Jim saw this in action the first time he was asked to participate with him on a pier design project. Tom Wosser, president of the company at the time, approached Jim on a Friday about a potential design project for the Oakland Estuary. He suggested he speak with Henry about it, recalling that Henry had done some pier work in the 50s. Jim caught Henry in his office late on a Friday morning. After explaining the Port of Oakland design project, Henry discussed in detail previous pier designs he had done nearly 30 years ago. Henry also provided Jim with suggestions for in-house resources he could use and where he’d find more information on pier design.

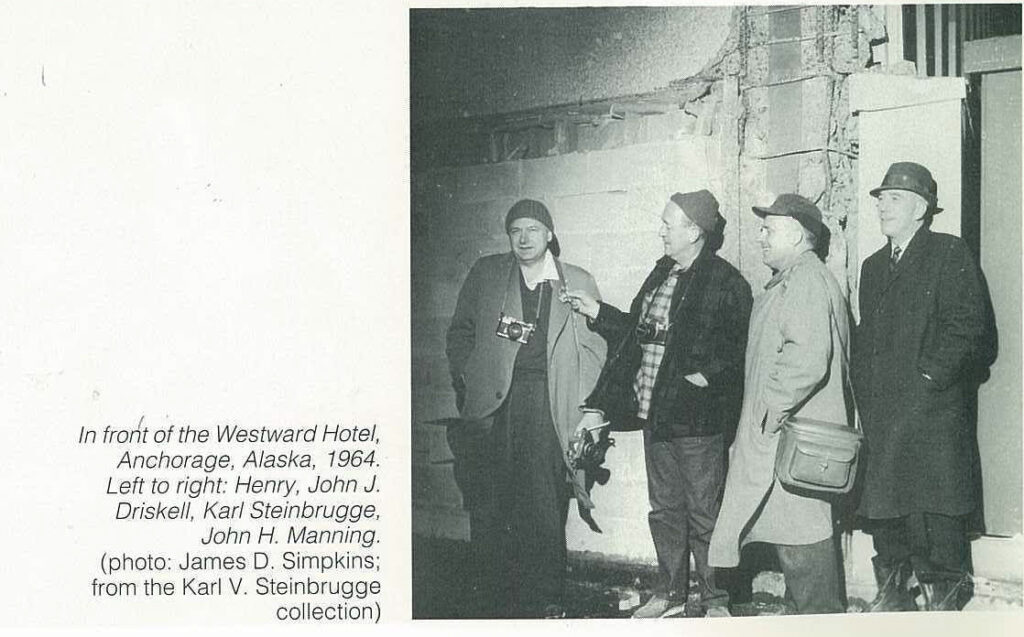

Photo from the EERI series Connections: The EERI Oral History Series – Henry J. Degenkolb

The next Monday morning, Jim came into the office and found a pile of reference documents on his desk (with some notes in the margins), a set of pier design calculations, sketches of connection details, and a cost estimate for the whole effort. Over the weekend, curiosity, interest, and passion had gotten the best of Henry—and he’d completed the entire project. Once done, he’d left it on Jim’s desk to do the rest, leaving no note nor explanation.

Henry’s interests weren’t strictly limited to structural engineering. He was an intensely curious man and dedicated tinkerer; his home was full of various types of projects. The basement housed a printing press, where, every month, he’d print up newsletters for structural engineering organizations. He loved photography and had a full darkroom where he could develop his own film. Even within the realms of engineering, Henry was always trying to learn more. Both of his brothers, Oris and John, were engineers as well. Oris was a bridge and traffic engineer while John was a fire engineer. Henry made sure that Degenkolb Engineers had all the technical papers about fire and bridge engineering; he liked to read the latest articles so he could talk over the topics with his brothers.

Henry examining structural damage to a building.

Henry’s inquisitive nature made him an excellent mentor in the field of structural engineering. He sought out opportunities to meet with colleagues and discuss work of the day. Every Friday, Henry attended the local Engineer’s Club lunch in the Bechtel Building. It was a casual gathering of contemporaries and competitors, but the overall atmosphere was collegial and synergetic. Engineers from all over the city would talk excitedly about projects they were working on, sharing ideas as peers. After lunch, the group would make their way to the bar, where they’d have a drink or two, and then Henry would return to Degenkolb’s offices with a bottle of rye whiskey in hand. He’d put the bottle out on the table so the staff could have a drink and play cards late into the afternoon.

Henry’s passion for structural engineering could be seen in action just after the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989. He’d been seriously ill for some time and, when the earthquake hit, was confined to his home, unable to go out into the field and assess the damage for himself. For someone who’d dedicated his life to improving the seismic performance of buildings in San Francisco, being unable to go out into the field after the very event that he’d been anticipating was a frustrating position indeed. So, if he couldn’t see it firsthand, he made sure that at least he would get first-hand descriptions of how structures had fared. He called his secretary and had her set up a schedule to have the engineers come to him and describe what they were seeing in the field. Jim and his cohorts went to Henry’s bedside and recounted their sights. They described buildings that had performed well, and others that had not. “Oh, I knew that one wouldn’t do well,” he’d say, his intuition for structural engineering playing out with real-world results.

Henry liked to stress the importance of a good design from the start. In an interview with Stanley Scott for the EERI Oral History Series, Connections, Henry said: “What you start out, what your assumptions are, largely determine. With the right way of doing things, if a system is inherently good, it really doesn’t matter whether it’s a little stronger or not. But if you weaken it to the point where you permit bad details or poor anchorages, you only save peanuts while increasing the hazard tremendously… I think it’s like almost anything else—if you start off on the right path, it’s not hard to do things right.” This philosophy is something that Jim tries to carry forward with him today and pass down to younger engineers, and what he sees as one of the lasting legacies that Henry has left at the firm that bears his name.